Summary

The pandemic situation in continental Europe has been worsening rapidly, and I felt that I should update some country comparisons in a dedicated post.

It confirms that the sourcing of data for a Coronavirus model of any given country is a very specific task nowadays, given the considerable differences in the underlying demographics, cultures, Government actions such as NPIs (Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions) and vaccination, and public responses in the various countries.

This blog post isn’t looking at the modelling per se, but concentrates on the very different outcomes we are seeing across Europe, looking at some the underlying data to understand the reasons why.

It shows that the UK’s position vs. Europe is rooted in our higher infection rate from the July 19th “Freedom Day”, together with the successful recent rollout of the Booster vaccination programme, building on the leading position the UK has had in vaccination since the end of 2020.

It’s a complicated picture. Several European countries have also achieved high vaccination rates, but it’s also about earlier 2021 events. UK vaccination starting back in December 2020, well before the Delta variant hit in April 2021. The UK’s summer infection rates, following the successive removal of lockdown mitigations; and the UK was one of the earliest with the booster programme, thanks to that early start of the vaccination programme in the UK. The poise impact of the booster programme suggests that vaccines should really be regarded as a “3-shot” regimen, not 2 shots.

But there remain internal and external ethical and moral questions about what is the right approach for a country to get to herd immunity itself, and what should be the policies of any given country with regard to 200 other countries worldwide, including the third world, who need vaccines as much as anyone. Put briefly, no-one is safe until we are all safe.

At the very least, therefore, there is a benevolent self-interest motivation to help others, as Covid shows that we are all dependent on each other to keep ourselves safe, as has just been made clear again by the reported restrictions on travel to the UK from six African countries following the discovery of the worrying “Omicron” variant B.1.1.529, now under investigation in South Africa.

The EU situation

I’ll cover the UK shortly, but just reading the newspapers and following social media, we can see that the situation in some European countries is becoming dire.

The BBC reports that case rates in some European countries are rising quite quickly, compared to the UK, leading some countries to re-introduce some major NPI measures – not always calling them “lockdown”, a term becoming politically unacceptable nowadays. The UK’s own Government Coronavirus news page, which reports in detail on the UK situation, also reports the following chart for Europe.

Four of the countries with the most steeply increasing case rates are taking special measures, as are some others. The measures taken in some of these countries have led to mass demonstrations, and, in some cases, violence.

Austria‘s government ordered about two million people not fully vaccinated against Covid-19 to stay at home as the country experienced a record high in infections. Austria has one of the lowest vaccination rates in western Europe.

The measures, which came into force on 15th November, prevented unvaccinated people over the age of 12 from leaving their homes except to work, buy groceries, go for a walk or attend medical appointments, such as getting vaccinated. Jabs became mandatory for health professionals. Unvaccinated students were also told to stay away from campus for two weeks. On 19th November, the Austrian Government announced that from Monday 22nd November, Austria will move into complete lockdown for three weeks.

The Netherlands re-introduced 7pm closures for restaurants, cafés and non-essential shops, restrictions on attendance at mass events, advice on working from home and limitations on numbers of domestic visitors.

Euronews reports that “Germany‘s disease control centre is calling for people to cancel or avoid large events and to reduce their contact with others”.

In its report on Belgium, Euronews stated on 26th October that the Belgian government had extended mandatory mask-wearing in indoor settings, and encouraged people to be more “prudent”, but stated that they would not limit activities. They also extended use of the health pass — the COVID safe ticket — to more events.

This is all despite the fact that vaccinations rates have been quite high in those, and in many other European countries, some with more percentage coverage than the UK.

Many other factors, are involved, as we have seen in the UK, including the proportion of the population that have received booster jabs.

Euronews reports that some eastern European countries are faring even more poorly with the pandemic than western ones, as this Financial Times article discusses.

It shows these charts for eastern European countries, for cases per 100,000 and deaths per million, highlighting that “the figures contrast starkly with western Europe, where death rates are about a tenth of those in the east and stand at less than one per million in several countries”.

We can see that Romania heads the chart for deaths per million of population. The Euronews report on Romania states that “Fewer than 50% of the Romanian population is fully vaccinated, and health authorities have repeatedly called for an increase in vaccination rates, saying “prevention is the best protection”.”

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) put the new wave down to the more transmissible Delta variant, middling vaccination rates and a relaxation of social distancing measures in some European countries.

It predicts that only countries with vaccination rates of over 80 per cent – such as Spain, Portugal and Malta – will escape pressures over winter. “These few countries are likely seeing very little waves with a very low impact in terms of hospitalisations and mortality,” it said.

They are not far off with that assessment of the required vaccination rate. Delta, with R0 ⩬ 7, requires Herd Immunity H% = (1-1/R0)x100% ⩬ 85%.

The 80% mentioned by ECDC, however, is less than the 85% absolute minimum, and there are fears that 85% will be very hard to reach. In many countries,including the UK, the youngest children (who don’t suffer badly with Covid-19 themselves, but when infected, can pass it on) aren’t vaccinated, because the balance of risk to them doesn’t justify it.

There also is a measurable proportion of vaccine hesitants, for whatever reason, genuinely medical or otherwise, which further reduces the potential for complete vaccination coverage.

Perhaps for these reasons, with Covid-19 infections becoming an even higher risk, the European Union drugs regulator has just authorised Pfizer’s coronavirus vaccine for use on children aged from 5 to 11 in the EU.

It clears the way for jabs to be administered to millions of school children on the continent amid this new wave of infections sweeping across Europe. The agency said it “recommended granting an extension of indication for the COVID-19 vaccine Comirnaty to include use in children aged five to 11”.

The vaccine, Comirnaty, will be given in two doses of 10 micrograms three weeks apart as an injection in the upper arm. The EMA recommended adult doses contain 30 micrograms.

We can see the concerning picture for mortality across European countries in the following chart, showing things generally worse in eastern Europe compared with the west.

The current situation in the UK

Vaccination has allowed Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to be reduced in the UK, culminating in the UK Government’s “Freedom Day” on July 19th, so that as long as a new variant doesn’t develop with more damaging transmission rate, virulence or mortality, social and working lives are returning gradually towards pre-pandemic levels. There is, however, already a new player in town, AY.4.2, with another – Omicron – threatened.

Sub-variant AY.4.2

So far, despite representing 10-15% of Delta infections in the UK, the latest sub-variant of Delta, initially known as AY.4.2, later designated as VUI-21OCT-01, and described in detail in the UK Government Technical Briefing 26, is not thought likely to become significant, as I reported last time. This chart for England from the Briefing shows Delta sub-variant AY.4.2 in light blue, with the AY.4 lineage as a whole in dark blue.

The Omicron variant

Just as we thought it might be safe to go back into the water, however, news media have just announced a new variant in South Africa, designated B.1.1.529, which, given that South Africa is quite well vaccinated, has been spreading surprisingly quickly, as shown in the chart below. It has also been detected in Botswana and Hong Kong.

Since Delta, there have been eight other variants named sequentially after letters of the Greek alphabet by the World Health Organisation (WHO), but none have triggered this much worry. B.1.1.529, now designated “Omicron” (not “Nu” or “Xi“) by the WHO, is causing alarm.

This is because of the number of mutations it carries on its spikes, suggesting that it might transmit faster and/or have the potential to escape immunity.

Speaking at a South African government press conference Professor Tulio de Oliveira, from Stellenbosch University, said that this variant had a “very unusual constellation of mutations” including more than 30 in the crucial spike protein, which the vaccines target. He said that this was a surprise.

Only a few dozen samples of the variant have been sequenced, in South Africa, Botswana and Hong Kong. But the first case in Europe, apparently, has just been detected in Belgium.

It is now reported that the UK Government, advised by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), have restricted travel to the UK with almost immediate effect from 6 countries, including South Africa, which indicates the level of concern.

The post – UK “Freedom Day” situation

In July, the average contacts per day per individual were reported by the BBC at about 4, compared with 10 pre-pandemic, which would be consistent with reduced infection transmission rates. Even so, most professional modellers in the UK have been surprised that infection rates have been fairly low so far, following the July 19th “Freedom Day” removal of all lockdown measures, compared with their expectations. Some of their prior expectations of 100,000 cases per day seemed very high to me.

The following Chart 207 shows only Reported Cases, Active cases and Deaths, where a very slight flattening of the formerly slightly rising Reported Active cases can be discerned. Note for reference below that UK relaxations of NPIs this year took place on March 29th, April 12th, May 17th, and the complete removal of NPIs on July 19th (delayed four weeks from the initially planned June 21st). These were, respectively, Days 423, 437, 472 and 535 since the beginning of the pandemic in the UK.

The chart shows growth in active cases (and therefore total cases) starting to steepen at about Day 500, and the inevitable follow-on increase in the death rate starting soon after, at about Day 530.

It seems to me that the May 17th and July 19th NPI relaxations were specific Government choices made in the knowledge that this might be the impact. I show below that this decision is credited, rightly or wrongly, by many experts for putting the UK in a better position than Europe just now.

The Government has since continued to state that they see no evidence in the data for their documented plan B yet.

As I mentioned above, most modellers advising Government are surprised that infection rates have been fairly low so far, certainly compared with some expectations of 100,000 new active cases per day, which seemed high to me.

What does surprise me is that new Active cases have sustained a rate of 30k to 50k per day for several weeks, presumably just about matching the Recovery rate, keeping Active cases on quite a consistent plateau, along with a slowly increasing death rate, at about 150 deaths per day at present. As I reported in my November 8th post, my own model predicted (on a variety of parametric assumptions) that there should be a peak in active cases around now, followed by a decline, which you can see later in this blog post.

Hospital admissions, which have fluctuated at between 700 and 1,000 a day for nearly four months now, are now starting to trend down in the UK as booster vaccines take effect.

There are worries that as winter approaches, and people spend more time indoors, with the festive season approaching, case rates might increase. There is parallel concern that winter ‘flu, having been absent last year, leading to a lack of immunity, may come back with greater severity this year, with both illnesses putting the NHS under pressure again.

Contrasting the UK with Europe

The UK Prime Minister and other ministers continue to say that they see no need yet for the “Plan B” that appears as a potential option on the Government’s coronavirus website, while hinting that Europe’s woes might yet wash up on our shores, although most experts think this unlikely.

The Times newspaper quoted a UK Government source on November 20th as arguing that despite criticism of high case rates in the summer, it was helping to avoid a surge now. “Opening up in the summer was clearly the right call. But what Europe shows is there is absolutely zero room for complacency. The disease can move quickly, so the road ahead is not straightforward.”

We will see below that some experts think that the UK is now better protected, not only thanks to vaccination, but also because immunity was enhanced by our high case rates earlier in the year, shown above.

Cases inevitably lead to a proportion of Covid-19 deaths, and up to 15,000 Covid-19 deaths have also been recorded since Freedom Day on July 19. Higher case rates though the summer will have meant higher death rates later.

This highlights the moral and ethical quandary involved in achieving national immunity (the notorious “herd immunity”), even if only partly through natural infection, with most people becoming immune by vaccination.

UK expert opinion, and the importance of booster vaccination

Imperial College historical outlook, June 2020

I became aware of one key expert opinion, which goes back to June 2020, when I asked the Imperial College team why it appeared from their work that the combination of three effective NPI measures in their model gave worse outcomes than the combination of any two of them.

That information was in the table below, from their well-known Report 9 on March 16th 2020, which, together with advice from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and from others, forced the UK Government to give up their (denied) strategy of “herd immunity” and to go for a lockdown-based approach, at some level.

The new strategy was to keep the NHS from being overloaded, and to ride out the pandemic storm until (as it turned out) a pharmacological (and the only ethical and feasible) solution came to hand – vaccines. That table is here:

The table is helpfully colour-coded: green for more effective combinations of NPI measures, ranging through yellow and orange, to red for less effective ones.

You can see 3 columns at the centre of the table, where either of CI_HQ or CI_SD are better, as combinations of two broad sets of NPIs, than CI_HQ_SD, all three of them together.

Similarly, in the last two columns, three measures, CI_HQ_SDL70, are broadly better than four, PC_ CI_HQ_SDL70. The answer that came back was:

“It’s a dynamical phenomenon. Remember mitigation is a set of temporary measures. The best you can do if measures are temporary is go from the “final size” of the unmitigated epidemic to a size which just gives herd immunity.

“If interventions are “too” effective during the mitigation period (like CI_HQ_SD), they reduce transmission to the extent that herd immunity isn’t reached when they are lifted, leading to a substantial second wave.

“Put another way, there is an optimal effectiveness of mitigation interventions which is <100%. That is CI_HQ_SDOL70 for the range of mitigation measures looked at in the report. While for suppression, one wants the most effective set of interventions possible.

“All of this is predicated on people gaining immunity, of course, If immunity isn’t relatively long-lived (>1 year), mitigation becomes an (even) worse policy option.“

I have highlighted what I think is the key statement in this response over a year ago, in June 2020. I think that this has also informed the spring and summer 2021 strategy regarding our UK NPI relaxations, on March 29th, April 12th, May 17th, and the removal of all remaining NPIs on July 19th (which had been delayed 4 weeks from 21st June 2021) mentioned above.

The gaps of several weeks between each step of these NPI relaxations were to enable their successive effects to be assessed, and the UK Government did, in the event, delay the last one by four weeks. Both my model, and the reported data show that period to have been pivotal in the growth of case number and deaths.

I have to admit that, before that Imperial College response to my query, I had not considered (for my model) the concept that short term gain could be at the expense of a better long term outcome.

Achieving herd immunity

Of course I was aware that an initial and total “herd immunity” approach per se was a busted flush, but at some point, for a given variant, with a given starting R0 value, herd immunity, either through natural infection or vaccination, must be achieved. And for higher values of R0 it has to be at a high percentage as mentioned above. Delta, with R0 ⩬ 7, requires Herd Immunity H% = (1-1/R0)x100% ⩬ 85%, whereas for the original variant with R0 ⩬ 2.5, the required H% ⩬ 60%, or for the Alpha variant with R0 ⩬ 4, the required H% ⩬ 75%.

The human cost, for a lethal disease such as Covid-19, as well as the required immunity percentage, H were going to be far too high to achieve herd immunity by natural infection; such an initial herd immunity strategy was simply unethical, immoral and actually unattainable. No country has achieved more than 20% Covid immunity by natural infection.

For a less harmful infection, such as chicken pox, with R0 ⩬ 18 or so, herd immunity H would be ~95%, but in this case, we can “let it rip”, and even have chicken pox parties to get it out of the way (as we did when I was a child), because there is negligible mortality from chicken pox.

What we are seeing now in the UK is that a mixed approach of protecting the population, to a reasonable(?) degree, while allowing some infection to spread seems to have prepared the UK, towards the end of this year, to be in a better position than many other countries, now that the extent of vaccination deployment has reached such a high level.

We have seen above that in some European countries, despite some high vaccination rates (but also some low ones) there often doesn’t seem to be a sufficient natural immunity baseline onto which vaccination immunity is added, to keep the very contagious Delta variant of Covid-19 at bay.

It may well be that booster vaccinations, with their early and rapid delivery, are a “game-changer”, as we see below that some experts think, in that they aren’t just a top-up, but do add a significant degree of extra protection, and have therefore also played their part in distinguishing the UK’s outcomes from Europe’s.

What are experts saying now?

Many experts are saying now that the UK is in a better position, because of those high case rates we have had through the summer, not despite them.

Imperial College’s Prof Neil Ferguson, is reported by the BBC to have said that the UK is unlikely to experience a “catastrophic winter wave” of COVID cases that would require a Christmas lockdown similar to last year. He also indicated that booster jabs for younger people, after the priority groups, would help.

The University of Oxford’s Professor Sir John Bell, is reported in the Times as saying said that despite soaring cases in the rest of Europe, Britons should be safe to order their Christmas turkeys because there was more immunity in the population. “One of the interesting things is that it may well be that the delay in lockdown in the UK, the pretty extensive level of disease, has given us longer-term protection.“

Graham Medley, of the London School of Medicine and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), who chairs the UK Government’s advisory SAGE Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies, was reported by The Times as saying that the size of the winter Covid wave would come down, owing to five factors. After vaccination [first], he says that reducing transmission is crucial. “This means [second] testing frequently, especially before and after events with multiple people. Third, if you test positive, then stay isolated, and [fourth] tell others that you have been with them so they can test or isolate themselves as well.”

His final [fifth] factor is protecting older and more vulnerable people by ensuring those carrying the virus avoid them.

As an older person myself, I’m not sure that I completely buy the feasibility or reliability of infected people avoiding me, other than through my own self-isolation. I would be more confident of the first four protocols.

The fifth was a “refinement” of his statement a year ago, which I reported in my October 29th 2020 blog post, when Prof Medley said, in a narrative piece in the Lancet “There have been increasing suggestions that one option is to simply protect everyone who is at risk of infection and allow the epidemic to spread in those at low risk…I noted that this approach is conceptually appealing but impossible in practice. It is not a strategy I endorse.“

I had also pointed out the problems with isolating older people in my 22nd September 2020 blog post, citing work on social mixing by Adam Kucharski, and his Twitter thread, when he said “There have been attempts to have ‘shielding’ of risk groups (either explicitly or implicitly) in many countries. But large epidemics have still tended to result in infection in these groups, because not all transmission routes were prevented.” Or, to put it briefly, children do visit their grandparents.

Paul Hunter, Professor in Medicine at the University of East Anglia, believes that continental Europe is now behind the UK. “The UK is now in a better position in terms of immunity than most of Europe because we’ve had a lot of infections and we’re now rolling out the booster jab,” he said.

The booster jab matters

“Booster jab matters” was the title of my October 19th blog post, and the play on words wasn’t accidental. The UK booster vaccination programme has almost certainly already made a big difference, in the context of waning immunity from the earlier vaccination phases. Third jabs started quite early in the UK, just as the original vaccinations did.

There is a view that the booster jab is a game-changer, and that a third dose is not just a “top-up”. It completes the course, offering immunity levels that two jabs alone could not reach. Britain is giving booster doses faster than the rest of Europe, with more than twice as many doses per head as Austria, France or Germany.

Prof Paul Hunter said: “The early signs are that the booster provides substantially greater protection against infection and symptomatic illness than any two-dose regime. That protection may still wane but it will last longer than we’ve seen for two doses.”

Is Paul Hunter right, or does immunity waning have the same degrading effect on immunity after three jabs? There is an argument that, as long at the virus doesn’t mutate significantly, even as immunity wanes, the body has already learned how to react to the infection, and can still respond accordingly. This was supported by two Nature articles, the first of which, this 24th May Nature article, saying

“Consistently, circulating resting memory B cells directed against SARS-CoV-2 S were detected in the convalescent individuals. Overall, our results indicate that mild infection with SARS-CoV-2 induces robust antigen-specific, long-lived humoral immune memory in humans“.

A later Nature article said on 14th October “The most recent studies suggest that hybrid immunity is, at least partly, due to immune players called memory B cells. The bulk of antibodies made after infection or vaccination come from short-lived cells called plasmablasts, and antibody levels fall when these cells inevitably die off. Once plasmablasts are gone, the main source of antibodies becomes much rarer memory B cells that are triggered by either infection or vaccination.”

Age-related infection rates in the UK

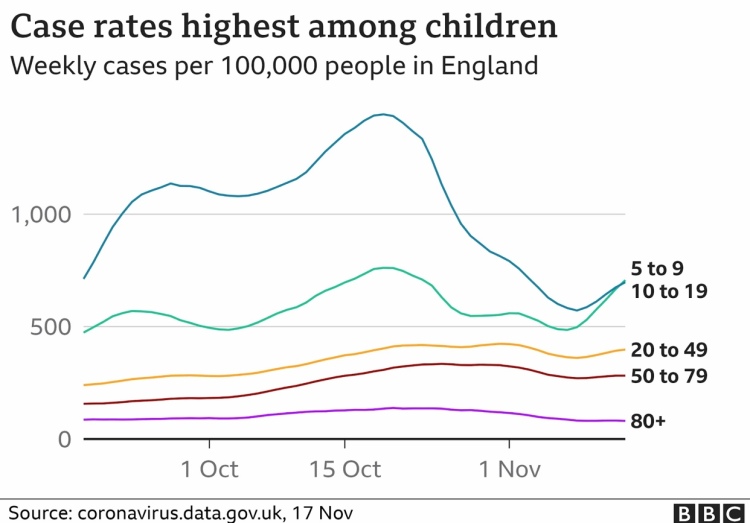

The following chart confirms what I indicated earlier, that case rates per 100,000 of the adult population in the UK are beginning to fall slightly at the moment. I emphasise that this is a chart for recent months in 2021. If it were to extend back to 2020, prior to the vaccination programme, it would show a very different 2020 picture as between the older/vulnerable groups vs. the rest.

Vaccination during 2021, including the recent booster programme, for which older and vulnerable people are again a priority, has made a huge positive difference in outcomes for the older groups, as I showed in my comparative model charts for four population groups in the UK in my November 8th blog post.

A further refinement of this chart was subsequently published, showing that children aged 5-9 (unvaccinated) now lead the case rates in England, having just overtaken children aged 10-15. It’s a complex and moving (in both senses) picture – in some age ranges it is a fluctuating picture. Now that Europe’s EMA have approved vaccination for children aged 5-11, I wonder if the UK might move further on this aspect of the vaccination programme in the UK, since infection rates in children are so high.

Over the course of the pandemic in the UK, despite their higher infection rates, children have suffered much less from the symptoms Covid-19 than adults. The NHS announced that children between 12-15 would be offered vaccination, and this started on 22nd September in the UK.

The UK’s Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) advises the Government about the vaccination of children, and currently it is felt that the relative risk/benefit to children 11 and under, as between vaccination and catching Covid-19, isn’t sufficiently clear for them to recommend vaccination.

Implications for country-based modelling

This all serves to indicate that the detailed country data behind any modelling is very important. As we look at the charts of reported daily cases in many EU countries, the outcomes can be quite counter-intuitive, as we see for the UK, where proportionate case growth by age-range has moved from the older, to younger adults, and now to the very young, because of the specific movements in phasing and rates of vaccination across age and vulnerability groups.

The widely varying country outcomes across Europe show a) that pandemic modelling has to be very specific by country, not only because of the widely varying vaccination contexts, but also b) that outcomes vary by age/vulnerability group, which means that countries’ demographic differences are important; c) that parametric modelling is important to help decision-makers in different countries to project the differential effects of their various mixes of potential mitigations; and d) that it is therefore important – and a lot of work – to ensure all such required data is available to a model to make any projections valid and useful.

Remaining hospitalisation and deaths burden in Europe – LSHTM

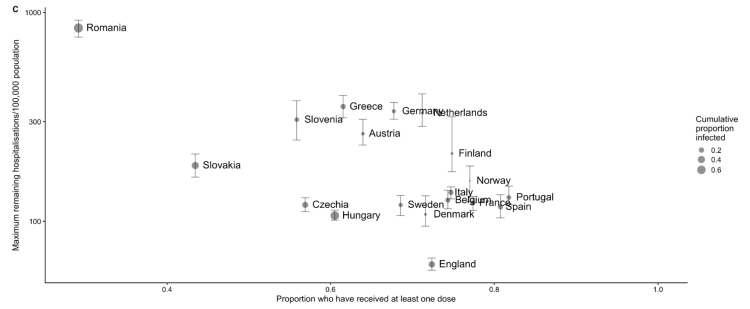

A recent study by the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases team at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) has addressed the questions “what is the likely maximum burden of deaths and hospitalisations from the pandemic in the UK? How does this compare to other countries in Europe?”

The study takes into account the levels of vaccination here and in other countries, by population age breakdowns, and the proportion of each population segment that has been infected in the past. Different vaccine efficacies and immunity waning aren’t included, and no allowance is made for the appearance of a new variant, or for significant growth of AY.4.2.

In a sense it is looking at how much “headroom” the current SARS-Cov-2 infection has left in any individual country, by assuming that everyone in the population were exposed to COVID immedialely; it’s not a prediction of what is going to happen. Just as my own forecasts, it calibrates what could happen under certain parametric assumptions.

For the UK it chooses England as the source of data; it the largest of the four home UK countries, who all have slightly different ways of gathering data.

It found that in England there might be 10,479 more deaths under these assumptions. Given the broad vaccination, NPI, demographic and cultural similarities in the home countries, this number could be scaled up for each of the home countries in the UK, and for the UK as a whole, which shows the UK figure might equivalently be 12,500.

Here is the chart for England showing the potential vs. the history, which makes clear that the model projection is for less deaths than we have had since May 2021 until now .

The study goes on to compare England with other European countries, just as I have been comparing the UK with Europe for the pandemic history. It shows generally the same countries as before with the worst outcomes in deaths per 100,000 of population, and a relatively more encouraging outlook for England (and, by extension, for the UK).

Finally, I add one of the study report’s own charts, showing the potential hospitalisations for each country, on log y-scale with 95% Confidence interval bars.

These are indeed stark differences, but if you live in England (or the UK), it’s more reassuring, with the worst case model outlook being 19 more deaths per 100,000 population.

Look how much higher many other European countries are: Germany faces potential deaths of 137 per 100,000; the Netherlands 92 per 100k and Austria 60 per 100k. In some countries further afield the risk is higher still: in Greece the potential deaths are 151 per 100,000 and in Romania it’s 356 per 100,000, which isn’t surprising given the charts I have shown before for reported data.

The study’s lead author, Lloyd Chapman, was reported widely as saying that the relatively good prognosis for the UK was not cause for unalloyed congratulations. “In a sense we paid a very high price for being further along a path towards having a high level of immunity in the population,” he said. “Whether that was the right strategy or not, I think in a way only time will tell.”

Commenting on the early delivery of vaccination and booster vaccinations, he also said: “England has done a good job of getting higher vaccination coverage in the eldest age groups.”

My model outcomes

My own model is delivering projections that show decline in serious cases over the forecast period. Modelled deaths (from Covid-19, not just mentioned on a death certificate) reach a maximum of around 149-153k by spring 2022, depending on assumptions about things such as vaccination volumes, Delta resistance to vaccines, immunity waning and vaccine hesitation. This represents possible increases from today’s reported 144,137 deaths (as of November 23rd) of between 5,000 and 9,000.

I show below my chart for model version UK029 (with variant v3 virulence and mortality as for previous variants, with vaccine efficacy to v3 at 85/95/100% for 1, 2 and 3 jabs compared with v1 and v2) showing an increase of 152,024 – 144137 = 7,887 deaths from today.

I have added no further NPI changes beyond the return to schools on September 1st, and I would think that some relaxations, followed by plan B, perhaps, would affect detailed outcomes. But the LSHTM study gives me some confidence that my model isn’t too far off.

The John Burn-Murdoch view

John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times has been publishing excellent analyses of the pandemic from the beginning, and posts on Twitter too.

His Twitter thread delves further into the LSHTM study outcomes, with several revealing charts. The first chart below illustrates the UK’s higher levels of infection-acquired immunity, which has cost many deaths, leading to the UK entering winter with fewer people exposed to the virus than other European countries, who will suffer more deaths going forward.

As I indicated before, JB-M says “that infection-acquired immunity comes at a grim cost. The UK has recorded more than 15,000 new Covid deaths since reopening on July 19“.

Here is another example of his well-constructed charts, this time dealing with the impact of the booster jab rollout.

He concludes that the UK’s booster programme of jabs has made the difference, going on to share the view that they should be regarded as the third dose in a “three jab regimen”, rather than being called boosters. Analysis like this will surely encourage the UK Government to strive to speed up the booster programme of vaccination.

These two charts pretty much summarise the two major factors resulting in the UK’s position vs. Europe as we approach 2022. There are more charts addressing other aspects of the pandemic on his Twitter feed.

A Scottish perspective

Living in Scotland as I do, with 8.5% or so of the UK population, I see some differences in the purely Scottish outcomes, since much of the pandemic management is local, even though the data driving my model’s outcomes are UK wide, and are therefore weighted by the populations across each of the home countries in the UK. These differences can often be timing differences, or differences of emphasis in the NPIs and public behaviour, and of course there will be demographic differences in population mix too, affecting vulnerabilities to infection.

There are some interesting comments at the Science Media Centre in early September regarding Scotland’s increasing case rates at that time. Prof Sheila Bird, at the MRC Biostatistics Unit, University of Cambridge, showed this table,

saying that “One possible reason for this divergence in recent weeks is Scotland’s earlier return to school – about 2 weeks ahead of England, but there are many factors which contribute to the prevalence of infection and so this is somewhat speculative, albeit anticipated.”

In my model, I had used the English date for the return to schools, September 1st, since this population is by far the largest of the four home UK countries.

Another, Prof James Naismith, Director of the Rosalind Franklin Institute, said “It was expected that Scotland’s school return (19th August) would lead to rise. Since English schools, did not go back until 1st September, the ONS data released today will not report on the effect of English school’s return. I would expect next week’s ONS data to show the beginning of a rise due to schools, this is because I expect England to follow Scotland.”

He also thought that “Too much political discussion focusses on the differences between the UK’s nations, with even scientists claiming one approach is much superior than another. The effect of these “differences” are rather small, looking at the data within England shows similar sized variations. The UK, either whole [or] as individual nations has had a depressingly terrible pandemic. The cumulative death rate (our world in data) is much higher than many comparable countries, not being the absolute worst is hardly worth bragging about.“

Prof Rowland Kao, University of Edinburgh, whom I have quoted several times before in my blog, notably regarding the cost in lives of the delayed lockdown in March 2020, said “Thus in many ways, Scotland’s experience can be viewed as a sneak peek into possible rises in cases that may occur in England over the next few weeks“.

There were more opinions from Prof Simon Clarke, University of Reading and Prof Kevin McConway of The Open University, who, like the others, are highly respected academic analysts, advisers and commentators around the pandemic.

Since those early September views, the BBC reports that in the last two months, the situation has changed again, with a large reduction in cases in Scotland, and just a modest increase in early November, as there has been in the UK generally.

The Times newspaper reports that “Covid deaths in Scotland are predicted to halve next month as vaccination levels continue to rise steadily. There were an average of 20 people with the coronavirus who died each day during the first week of November — however, an updated model from the Scottish government on how the country is coping with the pandemic expects that number to drop significantly.”

Along with much other detailed data, that weekly report number 77 from the Scottish Government, published on 4th November 2021, states that “Hospital and ICU occupancies are in a plateau. There continues to be uncertainty over hospital occupancy and intensive care in the next three weeks.”

The following chart from that report, covering case numbers in Scotland from July to early November, confirms the reductions shown above since early September.

The report also highlights that several data sources are used for the chart, with different cut-off points. As it says: “R, growth rate and incidence are as of 26th October (dashed line 1). The Scottish Contact Survey uses data to 3rd November (dashed line 2). The Scottish Government modelling of infections, hospitalisations and ICU beds, the long Covid analysis, the medium term projections and modelled rates of positive tests per 100K use data to 8th November (dashed line 3). Wastewater analysis uses data to 9th November (dashed line 4).”

Discussion

The requirement for such detailed and low-level data sourcing for a country shows why I have focused my modelling efforts almost totally on the UK, and not attempted multi-country modelling. I made an exception a year ago for the USA, when the situation wasn’t so complicated by multiple variants and vaccination, or even by any extensive federal programme of NPIs in the USA.

Nowadays we would surely have to analyse the USA on an aggregated, state-by-state basis, as, for example, vaccination attitudes vary so much across the political divide, and therefore across the geographical demographics, just as we have seen the national variations for Europe.

It is fair to say that even my modelling of the UK is a for an aggregate of four somewhat different home countries. One (England, 56.2m people) is much larger than the others, although my illustrations of the Scottish situation (for about 5.5m people) indicate that timing differences aren’t too large. Wales comprises 3.2m people, and Northern Ireland is 1.9m.

The Scottish National Health Service (NHS) is separately funded from England, but is part of the whole NHS in composition, spirit and ethos. Many of the English regions, as well as Wales and Northern Ireland, also exhibit differences of emphasis and delivery.

I make the judgement, however, that the principles of my modelling, and the relative importance of the model parameters, are valid UK-wide. Many of the experts quoted above, for example, expected England to follow Scotland(!) in relation to the two weeks timing difference in school terms.

Concluding thoughts

I do expect some changes in the context for the pandemic in the UK – via plan B or otherwise – but I don’t expect the extent of negative outcomes we had last year, now that so many of us are protected by vaccination, increasingly by three doses. Antiviral drugs such as Merck’s molnupiravir and Pfizer’s Paxlovid are also coming along, which look as if they will also be a big help, starting in early 2022.

I’m expecting, in the medium term, case and death rates to reduce, whatever the short term bumps (as Professor Jonathan Van-Tam, the deputy chief medical officer for England, warns us), leading to a situation where the epidemic becomes endemic, like winter ‘flu, which itself might be an issue this year, owing to the lack of immunity from last year.

All of this, however, is contingent on not seeing another highly transmissive (or more particularly, a vaccine evading) Covid-19 variant. Let’s hope that expert optimism about the Delta sub-variant AY.4.2 is justified, and that the recently announced Omicron variant B.1.1.529 from South Africa, isn’t as transmissive, virulent, vaccine-evading and/or as lethal some fear.

We don’t either want to suffer more of that antivaxxer nonsense that encourages vaccine hesitation amongst those who don’t have a medical reason to do so, any of which would tend to increase cases and deaths, by reducing and/or delaying the possibility of herd immunity being sustainably achieved.

3 thoughts on “The pandemic situation in Europe”